Sermon Advent 2 Year B

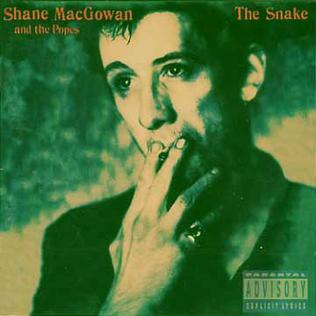

This week there was much coverage of the recent deaths of two great poets of our time. Benjamin Zephaniah – a brummie born and bred. A child of a Barbadian postman and a Jamaican nurse. And also Shane McGowan, lyricist and lead singer of the Anglo-Irish punk band the Pogues. Zephaniah an anarchist and Rastafarian. McGowan a toothless, often foul mouthed alcoholic. But, we know, as we look this week at the strange, wild man, clothed in camel hair, eater of locusts – that surprising people can point us towards God.

The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God – so starts Mark’s gospel as we have heard. But immediately what does this good news look like? It’s not a small child, in Mark there is no nativity, rather the good news starts with a reality call, in the wilderness. John the Baptist shouting and ranting, seeing the truth of the mess, sin and shame embedded in in human hearts – and offering to wash them clean. Not a gentle wipe mind, but a startling, breath taking plunge under the whirling water of the Jordan, with its mud and fish and chill.

Ladies and gentleman I give you – the good news!

God can use surprising people to point us to his presence.

All this week the Today programme has been replaying as part of its Advent calendar old audio clips of conversations with past guest editors. On Friday morning the clip they shared was Benjamin Zephaniah . A surprising poet – and certainly a surprising editor for radio 4. He left school at 13. Severely dyslexic his writing was inspired by sound and what he said was the politics of the street. A proclaimed anarchist he turned down an MBE with a furious denouncement of the connotation of ‘Empire’. But here he was, several years ago, in a BBC studio out doing John Humphries, arguing that our media only concentrates on bad news – and yet the world is full of good news. John Humphries was quite determined that good news was of no interest to people. But Zephaniah would not back down, the importance of good news to the human soul is essential. It shapes our world view, our behaviour and our hopes.

At present, if you are anything like me, the world seems overwhelmed by bad news. Maybe this has always been the case – but 24 hour media, updated every 20 minutes or so with a new angle, means we see so much of pain, horror and despair, it can be unbearable.

So, when we hear the cry in Isaiah this morning – that he, and maybe we, should be herald of good tidings – what does that mean, for us, in this time? As we work our way through Advent, preparing to retell again, for the 2023rd time (or something like that) the good news of the incarnation, the birth of Christ – what does that mean in places of deep sorrow – either in bombed out territories, or our tent lined cities, or our own homes, and hearts with their worries, and sorrows and cares. How is this good news? And if we believe it is, how should we proclaim it?

The problem with Christmas, is that it has become so twee. I am all for nativity plays, wonky haloed angel, snotty nosed shepherds. I love it when the lights are turned down at a Christingle and all the small faces are lit up by candles as we sing about the little Lord Jesus, laying down his sweet head. It has obvious appeal, and for a moment we are transported away from an adult knowledge of the world, into the innocence of childhood. But the problem is, of course, that doesn’t really cut it. Not when we find ourselves back in the full light of our own problems, or that of our loved ones, or flicking through the BBC news app. And appealing as this kind of Christmas is to those who might come into our churches at this time of year, but never think of turning up on Good Friday when God is hanging on the cross, the problem is the tweeness of a cartooned Christmas story as it often is, has little relevance when they are faced with their own dark night of a dreadful diagnosis, or past pain and betrayal, or are weeping through bereavement, fear, despair – or simply at the state of their own pitiful heart.

Well I think this is where I think we need our antiheroes. The unlikelys. The ones who know what it is like to live in the wilderness places – whether that’s the drunk tanks and gutters that Shane McGowan sang about and experienced, or the prejudice experienced by Benjamin Zephaniah over the colour of his skin, or a man driven literally wild by the spirit of God like John the Baptist.

I don’t think you have to be a complete weirdo to be a herald of good tidings. But I think what we learn from these people is an authenticity, a vulnerability, and an honesty about the darker, shadowy, sadder places of life. And we may not be rock stars, or famous poets, or the cousin of Jesus – but we can be authentic, vulnerable and honest.

The priest, Father Pat Gilbert, who led the Catholic funeral Mass for Shane McGowan on Friday in County Tipperary said in his sermon of the song writer that his poetry gave voice to people’s external experience and internal life. That he connected the cultural, the social, the theological, the spiritual into a coherent translation of what is happening all around us.

And if you’re not familiar with the songs of the Pogues they are not for the faint hearted. They tell tales of prostitutes, and drunkards, of the disillusioned and desolate. But by voicing this side of life, and as ordinary people would sing their songs in bawdy bars, and alone in bedrooms, these tales of human love and loss and life ‘gave us’ said the priest ‘hope, and heart and hankering’.

Hope and heart and hankering. Those words really struck me – and I wonder if that is exactly what the voice of the church – (and by that I mean you and I) are also meant to be. Not a saccharine, meaningless, tinsley, Christmas cardy herald of good tidings – but the ability to relate to others, in their humanity and in their fears and failures, with our own honesty, authenticity and vulnerability. Not pretending to have answers that we don’t have, but rather to stand alongside. Not to not shy away from some of the more uncomfortable realities of life, but in simply being and staying and acknowledging, we perhaps might reveal in our own imperfect, troubled and questioning lives – something of the strange and surprising presence of God.

And that it is in this God, who is discovered in the drunk punk and the dreadlocked poet, and the call of the wild man whose voice cries out to us today, that the good news, of this strange and surprising, honest and vulnerable, serving and suffering Christ – is good news indeed.

Hope and heart and hankering